Downfall (film)

| Downfall | |

|---|---|

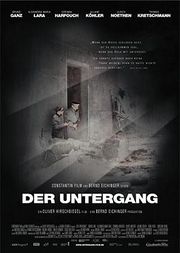

German release poster |

|

| Directed by | Oliver Hirschbiegel |

| Produced by | Bernd Eichinger |

| Written by | Joachim Fest Bernd Eichinger Traudl Junge Melissa Müller |

| Starring | Bruno Ganz Alexandra Maria Lara Corinna Harfouch Ulrich Matthes Juliane Köhler and Thomas Kretschmann |

| Music by | Stephan Zacharias |

| Cinematography | Rainer Klausmann |

| Editing by | Hans Funck |

| Distributed by | Constantin Film Newmarket Films (English subtitles) |

| Release date(s) | September 16, 2004 (Germany) February 18, 2005 (USA) |

| Running time | Theatrical cut: 155 minutes Extended cut: 178 minutes |

| Country | Germany Italy Austria |

| Language | German Russian |

| Budget | €13.5 million[1] |

| Gross revenue | $92,180,910[1] |

Downfall (German: Der Untergang) is a 2004 German/Italian/Austrian epic drama film directed by Oliver Hirschbiegel, depicting the final ten days of Adolf Hitler's life in his Berlin bunker and Nazi Germany in 1945.

The film was written by Bernd Eichinger, and based upon the books: Inside Hitler's Bunker, by historian Joachim Fest; Until the Final Hour, the memoirs of Traudl Junge, one of Hitler's secretaries; portions of Albert Speer's memoirs Inside the Third Reich; Hitler's Last Days: An Eye–Witness Account, by Gerhardt Boldt; Das Notlazarett Unter Der Reichskanzlei: Ein Arzt Erlebt Hitlers Ende in Berlin (memoirs) by Doctor Ernst-Günther Schenck; and Soldat: Reflections of a German Soldier, 1936–1949 (memoirs) by Siegfried Knappe.

The film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

Contents |

Plot

In 1942, a group of German secretaries are escorted to Adolf Hitler's (Bruno Ganz) compound in Rastenburg. After dictating to her in an indulgent, paternal manner, Hitler selects Traudl Junge (Alexandra Maria Lara). Shortly, the scene shifts to Hitler's 56th birthday on April 20, 1945. Secretary Traudl Junge is awakened in the Führerbunker by the sound of Soviet artillery. Later, Generals Wilhelm Burgdorf and Karl Koller indicate the Soviet Army is just 12 kilometres from the city centre. Later, at his birthday reception, Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Fegelein plead with Hitler to allow himself to be evacuated from the city. Instead, Hitler declares, "I will defeat them in Berlin, or face my downfall."

Meanwhile, S.S. Dr. Ernst-Gunther Schenck (Christian Berkel) is ordered by the high command to evacuate Berlin, as part of “Operation Clausewitz”. Instead, Schenck pleads with an SS general to be permitted to remain in order to look after the wounded and starving. The general grudgingly agrees to permit this. Schenck is requested by Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke (André Hennicke) to bring all the medical supplies he can obtain to the Reich Chancellery. While doing this, Schenck and his adjutant go to a hospital in search of medical supplies. They approach a tank position where a panzer commander informs them that everyone has left the hospital, and to be careful of the Russian troops in the area. Once inside the hospital, Schenck finds a room filled with elderly civilians. After retrieving what medical supplies are available, Schenck and his adjutant try without success to prevent the summary execution of two old men.

In another part of the city, a group of pre-pubescent Hitler Youth members continue a hopeless battle against Soviet tanks. Peter, a boy in the group, is vainly urged by his father to desert and flee the city. Later, Peter's unit is part of a group which is awarded the Iron Cross by Hitler.

In the bunker, Hitler discusses his new scorched earth policy with Albert Speer. The latter pleads for mercy for the German people, saying that Hitler's plans will return them to the Middle Ages. Unmoved, Hitler retorts that the German people have shown themselves weak and therefore do not deserve to survive. Later, Eva Braun holds a party for the bunker inhabitants up in the Reich Chancellery, but Soviet artillery shells ends the party early.

In the bunker, Hitler is briefed on the disintegrating defenses of Berlin. Unmoved, he announces that Waffen SS General Felix Steiner will soon arrive and drive the Red Army out of the city. However, he is then informed that Steiner couldn't mobilize enough men. Visibly shaken, Hitler dismisses all except Generals (Keitel, Jodl (Christian Redl), Krebs (Rolf Kanies), and Burgdorf), as well as Dr. Joseph Goebbels.

Throwing a massive tantrum, Hitler furiously accuses the Wehrmacht of sabotaging him from day one. He screams that the soldiers are all cowards and traitors and that the generals are, "the scum of the German people." He expresses regret at not executing the entire officer corps, like Joseph Stalin did during the Great Purge. At last, however, Hitler sinks into his chair and acknowledges that the war is lost. "If you think that this means I'll be abandoning Berlin," he snarls, "I'd rather shoot a bullet through my head."

Meanwhile, SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke is battling on the front lines with his troops when he observes a group of civilian volunteers running to their deaths in the streets. Mohnke asks one of his adjutants for a situation report. The officer informs him that the civilians are members of the Volkssturm, and they are under direct command of Dr. Joseph Goebbels. Disgusted, Mohnke orders the officer to get the Volkssturm out of the line of fire, and states he will take responsibility for doing so.

Mohnke makes his way back to the Reich Chancellery to confront Goebbels about the Volkssturm. Goebbels is in the bunker communications room talking to his wife Magda. Goebbels tells her to bring the children to the bunker and not to bring many toys or nightwear, which are no longer necessary. Thereafter, Mohnke tells Goebbels that the Volkssturm are nothing but cannon fodder for the Russians. In response, Goebbels bristles and informs Mohnke that their belief in “final victory” makes up for their lack of weapons and combat experience. Mohnke tells Goebbels that if these men do not have weapons their deaths are pointless. Goebbels informs Mohnke that he has no pity for them, adding, "The German people chose their fate and now their little throats are being cut."

Later Hitler, Eva, Traudl Junge, and Gerda discuss various means of suicide. Hitler proposes shooting oneself through the mouth, while Braun mentions taking cyanide. Hitler gives Gerda and Traudl one cyanide capsule each. Eva Braun and Magda Goebbels type goodbye letters, Braun to her sister and Goebbels to her adult son (from her former marriage) Harald Quandt. The child soldiers fight in the streets of Berlin, but to no avail. Peter, witnesses the death of all his squad mates and flees home to his parents, only to find that they have been murdered by death squads carrying out reprisals.

Meanwhile, Hitler has lost all sense of reality. General Wilhelm Keitel is ordered to find Admiral Karl Dönitz, who Hitler believes is gathering troops in the north, and help him plan an offensive to recover the Romanian oilfields. Oberscharführer Rochus Misch, Hitler's radio operator, receives a telegram from Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe. Martin Bormann reads the telegram to Hitler, where Göring asks permission to assume command of the Reich and asks for acknowledgment by 10 pm, at which time he will assume authority in the absence of a response. Walther Hewel tries to justify his actions, but Bormann and Goebbels declare Goering's actions to be high treason; Hitler orders Göring's arrest and removal from office.

Hitler summons General Robert Ritter von Greim (Dietrich Hollinderbäumer) and his mistress, ace pilot Hanna Reitsch, to the bunker. He appoints Ritter von Greim to be Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe, ordering him to rebuild it. During dinner, Hitler receives a report indicating that Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler (Ulrich Noethen) has just attempted to negotiate a peace settlement with the United States Army. Betrayed by the one man he trusted, Hitler explodes in another tearful outburst. He then orders Ritter von Greim and Reitsch to leave Berlin and rendezvous with Dönitz, who he is convinced is rallying troops and preparing a massive pincer strike with Field Marshal Albert Kesselring.

General Weidling reports that the Russians have broken through everywhere. There are no reserves and air support has ceased. Brigadeführer Mohnke reports that the Red Army is only 300 to 400 meters from the Reich Chancellery and that defending forces can hold out for a day or two at most. Before leaving, Hitler reassures the officers that General Walther Wenck will save them all. After he leaves the conference room, Weidling asks the other generals if it is truly possible for Wenck to attack; they all agree it is unlikely, even impossible, that Wenck will succeed, but do not wish to surrender.

The following day, Traudl takes dictation of the Führer's political testament. Hitler has ordered Joseph Goebbels to leave Berlin, but Goebbels intends to ignore the order. Hitler marries Eva Braun (Juliane Köhler). When Günsche later brings a reply from Keitel that the main armies are encircled or cannot continue their assault, Hitler states that he will never surrender. He also forbids all officers to surrender on pain of summary execution. Upon leaving the conference room Hitler gives Günsche the order to cremate his body and that of Eva Braun.

Eva affectionately gives Traudl one of her best coats and makes her promise to flee the Bunker. Hitler eats his final meal in silence with Constanze Manziarly and his secretaries. He bids farewell to the bunker staff, gives Magda his Golden Party Badge (marking original members of the NSDAP from February 27, 1925 to November 9, 1933, with numbers 1 to 100,000), and retires to his room with Eva. Although Magda pleads with him to change his mind, Hitler states, "Tomorrow, millions of people will curse me, but fate has taken its course."

Hitler and Eva retreat into their rooms and commit suicide with a pistol. Rather than live in a world without Nazism, Herr and Frau Goebbels poison their six children and commit suicide. All ten bodies are burned outside the bunker as the surrounding officers give the Nazi salute over the flames.

Most of the bunker survivors attempt to escape, but die at the hands of Red Army infantrymen. Weidling broadcasts to the soldiers and civilians in Berlin that he has called for a cease-fire with Marshall Georgy Zhukov; as every further hour of battle will merely postpone the inevitable. Meanwhile, Schenck and Hewel stay with Mohnke and his remaining SS troops, who debate on what to do once the Soviet troops arrive. Schenck tries to talk sense into Hewel, who promised Hitler that he would kill himself. However, when news reaches the officers that Berlin has been surrendered, Hewel promptly shoots himself. In the chaos of the city's fall, Traudl Junge makes her way through the Russian lines, escaping from Berlin by bicycle along with the child soldier Peter.

The susequent fates of the surviving characters are superimposed and the credits roll.

Cast

- Bruno Ganz as Adolf Hitler

- Alexandra Maria Lara as Traudl Junge

- Corinna Harfouch as Magda Goebbels

- Ulrich Matthes as Joseph Goebbels

- Juliane Köhler as Eva Braun

- Thomas Kretschmann as SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein

- Christian Redl as Generaloberst Alfred Jodl

- Heino Ferch as Albert Speer

- André Hennicke as SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke

- Ulrich Noethen as Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler

- Christian Berkel as Ernst-Günther Schenck

- Rolf Kanies as Hans Krebs

- Mattias Habich as Prof. Dr. Werner Haase

- Dietrich Hollinderbäumer as Generalfeldmarschall Robert Ritter von Greim

- Dieter Mann as Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel

- Justus von Dohnányi as Adolf Hitler's chief adjutant Wilhelm Burgdorf

- Igor Bubenchikov as Franz Schädle

- Gerald Alexander Held as Walther Hewel

Reception

While treatment of the Third Reich is still a sensitive subject among many Germans even 65 years after World War II, the film broke one of the last remaining taboos by its depiction of Adolf Hitler in a central role by a German speaking actor (as opposed to using actual film footage of Hitler). Ganz did four months of research to prepare for the role, studying a recording of Hitler in private conversation with Finnish Field Marshal Mannerheim, in order to properly mimic Hitler's conversational voice, and distinct Austrian accent.[2]

The film's impending release in 2004 provoked a debate in German film magazines and newspapers. The tabloid Bild asked "Are we allowed to show the monster as a human being?"

Concern about the film's depiction of Hitler led New Yorker film critic David Denby to note:[3]

As a piece of acting, Ganz's work is not just astounding, it's actually rather moving. But I have doubts about the way his virtuosity has been put to use. By emphasizing the painfulness of Hitler's defeat Ganz has [...] made the dictator into a plausible human being. Considered as biography, the achievement (if that's the right word) [...] is to insist that the monster was not invariably monstrous — that he was kind to his cook and his young female secretaries, loved his German shepherd, Blondi, and was surrounded by loyal subordinates. We get the point: Hitler was not a supernatural being; he was common clay raised to power by the desire of his followers. But is this observation a sufficient response to what Hitler actually did?

With respect to German uneasiness about "humanizing" Hitler, Denby said:[3]

A few journalists in [Germany] wondered aloud whether the "human" treatment of Hitler might not inadvertently aid the neo-Nazi movement. But in his many rants in [the film] Hitler says that the German people do not deserve to survive, that they have failed him by losing the war and must perish — not exactly the sentiments […] that would spark a recruitment drive. This Hitler may be human, but he's as utterly degraded a human being as has ever been shown on the screen, a man whose every impulse leads to annihilation.

After previewing the film, Hitler biographer Sir Ian Kershaw wrote in The Guardian:[4]

Knowing what I did of the bunker story, I found it hard to imagine that anyone (other than the usual neo-Nazi fringe) could possibly find Hitler a sympathetic figure during his bizarre last days. And to presume that it might be somehow dangerous to see him as a human being — well, what does that thought imply about the self-confidence of a stable, liberal democracy? Hitler was, after all, a human being, even if an especially obnoxious, detestable specimen. We well know that he could be kind and considerate to his secretaries, and with the next breath show cold ruthlessness, dispassionate brutality, in determining the deaths of millions.Of all the screen depictions of the Führer, even by famous actors, such as Alec Guinness or Anthony Hopkins, this is the only one which to me is compelling. Part of this is the voice. Ganz has Hitler's voice to near perfection. It is chillingly authentic.

Addressing other critics like Denby, Chicago Sun-Times film critic Roger Ebert wrote:[5]

Admiration I did not feel. Sympathy I felt in the sense that I would feel it for a rabid dog, while accepting that it must be destroyed. I do not feel the film provides 'a sufficient response to what Hitler actually did, because I feel no film can, and no response would be sufficient. As we regard this broken and pathetic Hitler, we realize that he did not alone create the Third Reich, but was the focus for a spontaneous uprising by many of the German people, fueled by racism, xenophobia, grandiosity and fear. He was skilled in the ways he exploited that feeling, and surrounded himself by gifted strategists and propagandists, but he was not a great man, simply one armed by fate to unleash unimaginable evil. It is useful to reflect that racism, xenophobia, grandiosity and fear are still with us, and the defeat of one of their manifestations does not inoculate us against others.

Hirschbiegel confirmed that the film's makers sought to give Hitler a three-dimensional personality.[6]

We know from all accounts that he was a very charming man — a man who managed to seduce a whole people into barbarism.

The film was nominated for the 2005 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in the 77th Academy Awards. The film also won the 2005 BBC Four World Cinema competition.[7]

The film is set mostly in and around the Führerbunker. Hirschbiegel made an effort to accurately reconstruct the look and atmosphere of the bunker through eyewitness accounts, survivors' memoirs and other historical sources. According to his commentary on the DVD, Der Untergang was filmed in Berlin, Munich, and in a district of Saint Petersburg, Russia, which, with its many buildings designed by German architects, was said to resemble many parts of 1940s Berlin. The film was ranked number 48 in Empire magazines "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.[8]

Criticism

The author Giles MacDonogh criticized the film for sympathetic portrayals of Wilhelm Mohnke and Ernst-Günther Schenck. Mohnke was rumored, but never proven, to have ordered the execution of a group of P.O.W.s in Normandy, while Schenck's experiments with medicinal plants in 1938 allegedly led to the deaths of a number of concentration camp prisoners.[9] In answer to this criticism, the film's director, in the DVD commentary, stated he did his own research and did not find the allegations as to Schenck to be convincing. Furthermore, Mohnke strongly denied the accusations against him, telling author Thomas Fischer, "I issued no orders not to take English prisoners or to execute prisoners."[10]

Wim Wenders called the filmmakers' collaboration with a history professor as "a strategic move to compile cultural capital and move the film beyond the reach of reprehensibility, challenge, or contradiction by writers or critics unwilling to engage the material other than by pointing out historical inaccuracies." He felt that the film said: "Wir wissen, wovon wir reden" ("We know what we're talking about"). Further, Wenders argued that Der Untergang presented an uncritical viewpoint toward the barbarism of its subject matter, and accused the filmmakers of Verharmlosung (rendering harmlessness). Wenders supported this observation with close readings of the film's first scene, and of Hitler's final scene, suggesting that in each case a particular set of cinematographic and editorial choices left each scene emotionally charged, resulting in a glorifying effect.[11]

The film's ending has also been the subject of criticism for not revealing what actually happened to several of the women who were present in the bunker. After the fall of Berlin an estimated 2 million German women were raped by the Soviets. In the film, the women manage to escape or are seemingly left unharmed when the Soviet soldiers arrive, whereas in reality several of the women were raped, some gang raped, and brutalized by the Soviet soldiers. Gerda Christian, Traudl Junge, Else Krüger and Constanze Manziarly, together with others, left the bunker on May 1 under SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke's leadership. This group slowly made its way north hoping to link up with a German army holdout on the Prinzenallee. The group, hiding in a cellar, was captured by the Soviets on the morning of May 2. Like millions of other German women,[12] Gerda Christian and Else Krüger were raped by soldiers of the Red Army. For these two women it was apparently in the woods near Berlin.[13] According to author James O'Donnell of The Bunker, Junge was also raped. However, Junge herself never mentioned this in her autobiography.[14]

While the film states that Manziarly vanished in 1945, Junge recounts her being taken into an U-Bahn tunnel by two Soviet soldiers, reassuring the group that "They want to see my papers." She was never seen again.[15]

Parodies

One scene in the film, in which Hitler launches into a furious tirade upon finally realizing that the war is truly lost, has become a staple of internet viral videos.[16] In these wildly anachronistic videos, the original audio of Ganz's voice is retained, but new subtitles are added so that he now seems to be reacting instead to some setback in present-day politics, sports, popular culture, etc. One parody depicted Hitler flying into a rage in response to being banned from Xbox Live.[17] This video accumulated a vast number of YouTube views and was posted on video game related sites.

By 2010, there were thousands of such parodies, including many in which a self-aware Hitler is incensed that people keep making Downfall parodies.[18]

The film's director, Oliver Hirschbiegel, spoke positively about these parodies in a 2010 interview with New York magazine, saying that many of them were funny and they were a fitting extension of the film's purpose: "The point of the film was to kick these terrible people off the throne that made them demons, making them real and their actions into reality. I think it's only fair if now it's taken as part of our history, and used for whatever purposes people like."[19] Nevertheless, Constantin Films has taken an "ambivalent" view of the parodies, and has asked video sites to remove many of them.[20] On April 21, 2010, the producers initiated a massive removal of parody videos on YouTube.[21] However, there has been a resurgence of the videos on the site since the mass removal.[22] On July 28, 2010, Constantin responded by issuing DMCA takedown notices on videos which had countered the blocking of the videos using a Fair Use argument.

Corynne McSherry, an attorney specializing in intellectual property and free speech issues[23] for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, stated "All the [Downfall parody videos] that I've seen are very strong Fair Use cases and so they're not infringing, and they shouldn't be taken down."[24]

See also

- Adolf Hitler in popular culture

- Operation Clausewitz

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "DOWNFALL". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=downfall.htm.

- ↑ Diver, Krysia and Moss, Stephen (2003-03-25). "Desperately seeking Adolf". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2005/mar/25/1. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Denby, David (2005-02-14). "David Denby's comments on Der Untergang". The New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/critics/cinema/?050214crci_cinema. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (September 17, 2004). "The human Hitler". London: The Guardian. http://film.guardian.co.uk/features/featurepages/0,4120,1306616,00.html. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (March 11, 2005). "Downfall". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20050310/REVIEWS/50222002/1023.

- ↑ Eckardt, Andy (September 16, 2004). "Film showing Hitler's soft side stirs controversy". NBC News. MSNBC. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/6019248/from/RL.1/.

- ↑ "Downfall wins BBC world film gong". BBC. 2006-01-26. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4652074.stm. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ↑ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema". Empire. http://www.empireonline.com/features/100-greatest-world-cinema-films/default.asp?film=48.

- ↑ MacDonogh, Giles; Henrik Eberle, Igor Saleyev, Otto Gunsche, Heinz Linge, Joseph Stalin, Fyodor Parparov (October 30, 2005). "xviii". In Matthias Uhl. The Hitler Book: The Secret Dossier Prepared For Stalin From The Interrogations of Hitler's Personal Aides (Hardcover ed.). PublicAffairs. p. 370. ISBN 1586483668.

- ↑ Fischer, Thomas. Soldiers of the Leibstandarte, J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. 2008, p 26.

- ↑ Wenders, Wim (October 21, 2004). "Tja, dann wollen wir mal". Die Zeit. http://www.zeit.de/2004/44/Untergang_n?. Retrieved July 5, 2009.(German)

- ↑ Hanna Schissler The Miracle Years: A Cultural History of West Germany, 1949-1968

- ↑ The Bunker, James Preston O'Donnell, Da Capo Press, 2001, ISBN 0306809583 page 211

- ↑ The Bunker, James Preston O'Donnell, Da Capo Press, 2001, ISBN 0306809583 page 293

- ↑ Junge, Gertraud. Until the Final Hour. Google. ISBN 9781559707282. http://books.google.com/books?id=ie1FsnzQkfUC&pg=PA219&dq=Constanze+Manziarly+just+want+to+see+my+papers. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- ↑ BBC: The rise, rise and rise of the Downfall Hitler parody

- ↑ Heffernan, Virginia (2008-10-24). "The Hitler Meme". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/26/magazine/26wwln-medium-t.html. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- ↑ Boutin, Paul (2010-02-25), "Video Mad Libs With the Right Software", The New York Times: B10, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/25/technology/personaltech/25basics.html?scp=1&sq=Downfall&st=cse, retrieved 2010-02-26

- ↑ Rosenblum, Emma (2010-01-15). "The Director of Downfall Speaks Out on All Those Angry YouTube Hitlers". New York. http://nymag.com/daily/entertainment/2010/01/the_director_of_downfall_on_al.html. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ↑ Finlo Rohrer (2010-04-13). "The rise, rise and rise of the Downfall Hitler parody". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/8617454.stm. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ↑ Finlo Rohrer (2010-04-21). "Downfall filmmakers want YouTube to take down Hitler spoofs". London: The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2010/apr/21/constantin-films-intellectual-property-spoofs. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ Parody, copyright law clash in online clips - San Francisco Chronicle

- ↑ http://www.eff.org/about/staff

- ↑ http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=126225405

Bibliography

- Fest, Joachim (2004). Inside Hitler's bunker : the last days of the Third Reich. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-13577-5.

- Junge, Traudl; Gertraud Junge, Melissa Müller, Anthea Bell (2004). Until the final hour: Hitler's last secretary. New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55970728-2.

- O'Donnell, James Preston (1978). The Bunker: The History of the Reich Chancellery Group. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-39525719-7.

- Vande Winkel, Roel (2007). "Hitler's Downfall, a film from Germany (Der Untergang, 2004)". In Engelen, Leen; Vande Winkel, Roel. Perspectives on European Film and History. Gent: Academia Press. pp. 182–219. ISBN 978-9-03821082-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=Z8HgGBVuZloC&printsec=frontcover#PPA182,M1. Retrieved April 18, 2009.

- Willi Bischof, ed (2005). Filmri:ss; Studien über den Film "Der Untergang". Münster: Unrast Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89771-435-9. (studies about the Film)

- Fischer, Thomas. "Soldiers Of the Leibstandarte." J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc., 2008. ISBN 978-0-921991-91-5.

External links

- Official website

- Der Untergang at the Internet Movie Database

- Der Untergang at Allmovie

- Der Untergang at Box Office Mojo

- Der Untergang at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Downfall - estimation - events - exchange Interviews, background and forum

- Interview with director Oliver Hirschbiegel

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||